Chapter Three

Honoring the Ancestors

and Those Who Have Passed On

Into The Spirit World William Apes (Pequot).

William Apes (Pequot). Born in 1798, Apes was described as an "Indian reformer in the Jackson Era." His autobiography, A Son of the Forest, published in 1831, made quite a splash in those days, though safely couched in the familiar terms of a Christian preacher. Although an assimilationist, he was certainly a pioneer among Native American authors. He did much to dispel the myth among whites that Native Americans were intellectually inferior. He died in New York City, April 9th, 1839 at the age of forty-one.

Joe Augustine (Micmac) Joe “White Owl” Augustine was a Micmac craftsperson and hunter, and medicine person who helped many people with this wonderful knowledge. He was a fluent speaker of his language and steeped in the tradition of the Wabanaki. He died of cancer in 2004 at a relatively young age.

Eunice Bauman-Nelson Ph.D. (Penobscot). Eunice is featured in two of Steven McFadden’s books, Wisdom Keepers, and Native American Wisdom. She was the younger sister of Molly Spotted Elk, the entertainer, and claimed to have been raised by her in her mother's absence. Many anthropologists came to see Molly at home, and Eunice became interested in getting degrees in anthropology, to study how white people lived. She was involved in graduate work in 1954 at NYU, but one day in the fall of 1954 she was crossing Waverly Street and looked up to see a very large old tree beside the path. She had an epiphanal moment, seeing how all people and all beings were like the tree with herself as one of the twigs. She stood frozen in the crosswalk for a long time, seeing how everything in the universe was connected, and in fact a single organism. When she came back to her body, she was a changed woman, and changed her program to study co-housing in indigenous cultures around the world, and also became a "Gandhist" and became a leading spokesperson for a Gandhist movement in the US. Although paved over, the Sapohannikan Trail was under her feet as she had that vision, an ancient Algunkeen trade route, and she never knew until I told her just one year before her death. That tree is still there, in Washington Square Park. Some of her papers are being stored at the Universty of Maine in Orono.

Chief Beaver (Lenape). See Tamaqua.

Charles "Chief" Bender (Chippewa). Born in Crow Wing County, Minnesota in 1884, this early 20th Century Chippewa baseball player pitched his way into the Hall of Fame at Cooperstown, and is considered one of the all-time greats, although you seldom hear about him today. To correct this situation, I will take this opportunity to give him his due, since no one else has in eighty years.

History remembers Bender as the inventor of the slider, which is a combination curve and fastball, used by every top pitcher today--most of whom learned it from someone who learned it from Bender--who was, for thirty-five years, also one of baseball’s greatest pitching coaches. When he coached for the Giants, Carl Hubbell was one of his students.

Encyclopedia Britannica and many other highly regarded sources credits him with the invention of the slider. The "slider" has been described by both Willy Mays and Hank Aaron as "the toughest pitch to hit." Ted Williams said it was "the greatest pitch in baseball..." and that it "had a big effect on the sport." The slider is one of the greatest offerings to baseball any individual ever gave, perhaps second only to Ruth’s popularization of the long ball. Today it is part of an esoteric oral tradition among major league pitchers, a difficult pitch to throw correctly, or to control, but which can change the outcome of a game or even a season when mastered.

Bender first tried the experimental pitch in a game against the Cleveland Indians on May 12, 1910. He hoped it would give him an edge, but like Alexander Graham Bell, George and Orville Wright, and Guglielmo Marconi of the same era, it is doubtful that even he realized how powerful his invention was, or how it would change the course of history. It was unhittable!

That game turned out to be his only no-hitter, but it was probably one of the most historic games ever pitched, kind of like The Little Big Horn of baseball, like Hiroshima, or any battle where a new weapon is unveiled; it changed the strategy of the game. Some called it ‘The Nickel Curve," due to the fact that the face on the nickel at that time bore a resemblance to Sitting Bull,

not the worst insult under the circumstances.

In 1910, his greatest season, Bender won 23 games (including the no-hitter) and allowing only 182 hits and 47 walks in 250 innings, with a 1.58 ERA, and a pathetic opposing team batting average of under .200! The slider still has that effect today on same-handed hitters.

No one has ever broken the “handcuffs” forged that day by the Ojibway kid.

But his influence on baseball goes far beyond that. Eddie Collins believed Bender, on a good day, to be just as fast as Walter Johnson. Ty Cobb called Bender "the brainiest pitcher he’d ever faced."

The aspiring pitcher Babe Ruth was fifteen years old at that time and probably saw Bender play, or at least heard him on radio. Ruth followed in his footsteps but never got his ERA as low as 1.58. Bender won the opening game of the World Series that year, throwing a one-hitter through 8 innings against the 104-win Cubs. (They’d actually won 530 games in five years.)

The stunned Cubs managed two more singles in the ninth, but the A’s won, and went on to win the Series.

As a league leading pitcher who was not bad at the plate, he may well have been a role model for the young Babe Ruth. Bender had 6 homers lifetime in the dead ball era plus 40 doubles, 10 triples, and smacked 243 total hits. Ruth produced similar stats during his years as a pitcher, 1915 to 1920. Many teams at that time scouted the reservation diamonds for great athletes even before they went to college. Lots of them made it into the majors. In most cases, their native origins were hidden from the public, but not "Chief" Bender. Like Hank Greenberg for Jewish players, and Jackie Robinson for black players, Bender held his temper and his pride in check under the racist tongue-lashings that were heaped upon him so that others could follow his shining example in years to come. He was proud to be Chippewa and America loved him.

How popular was he? When Bender faced off with Christy Mathewson in the first seven-game World Series in 1905, it established a crowd attendance record at a whopping 24,187. Bender pitched a five-hitter but lost 2 to 0 in that one. He faced Mathewson once again in the opening game of the 1911 World Series, and established yet another attendance record, a historic 38,281. (Both were at the Giants’ Polo Grounds. Mathewson facing anyone else always drew a smaller crowd. By the way, the Giants had special uniforms made for that one series.) Again, Bender pitched a five hitter but lost, this time 2 to 1. That attendance figure was broken the day Ruth started for Boston in the 1916 World Series, at home. It was not broken again until 1922 (just barely, with 38,551) in the "no-subway" series where both teams calling the Polo Grounds their home won the pennant. The next year, Yankee Stadium was opened as the first big "stadium," and a whole new era began, starring Babe Ruth.

Bender went on to pitch for the Baltimore Terrapins (Federal League, 1915), the Philadelphia Phillies again (1916-17), and much later, the Chicago White Sox (1925) He pitched in the 1905 World Series, the 1910 World Series, the 1911 World Series, the 1913 World Series, and lastly the 1914 World Series His world series pitching record is one of the best in history, and usually against the greatest opponents of the era; Christie Matthewson. (3x) Joe McGinnity, Mordecai Three Finger Brown, Red Ames, Rube Marquard, etc.

Bender started out at the Carlisle Indian School in 1898, the year Louis Socakalexis was

all the rage. Bender stayed there until 1901, playing football and baseball with equal spirit. Underclassman Jim Thorpe followed in Bender’s footsteps a few years later.

As a college kid at Dickinson College, Bender played semi-pro ball under the name Charles Albert with the Harrisburg Athletic Club to pay his bills. The Chicago Cubs (soon to earn the title "History’s Greatest Baseball Team") faced his ragtag club in an exhibition game in 1902, and when the eighteen-year old "Indian boy" beat them soundly, it sent shock waves throughout baseball. He signed with the hot-pitching Philadelphia A’s the following year at age nineteen (1903), and started 33 games. He won 17 of them, pitching 270 innings. He went on to win over 200 games in 12 years and led the A’s to five World Series contests, contributing to four World Series championships, and winning six World Series games,: #5 on the all-time Series win list.

He is also #6 on the all-time Series strike out list with 59.

Charles Bender (he never called himself "Chief" or signed it as his name) did not get

angry when people ridiculed him or used racist taunts. He just laughed and dismissed them as "foreigners." The outspoken Connie Mack, who described Bender as the best "must-win" pitcher he’d ever managed (he managed Lefty Grove, I might add, and a lot of other Hall of Famers), respectfully called him "Albert," Bender’s middle name, never “Chief.”

Bender kept his ERA under 2.00 for three straight years, from 1908 to 1910. In 1910, 1911 and 1914, he led the league in win-loss percentage in an era of great pitching, 23-5, 17-5, and 17-3 respectively. In 1905, he took part in the World Series called The Shutout Classic in which all five games were shutouts, however his was the only one for his team, and the only victory, a 3-0 four-hitter.

In 1911, Bender turned in one of the greatest World Series pitching performances of all time. He threw a five-hitter to open the Series, but lost the pitchers’ duel to Hall of Famer Mathewson. Bender won 4-2 in game four, and then pitched a four-hitter to win the final game for the A’s, 13-2, and their second straight World Championship. His Series ERA was an unbelievable 1.04 in three complete games. But the most amazing part about this athletic performance, which more than anything else won him a place in the Hall of Fame, was that

his brother John had died tragically only three weeks earlier, on September 25th.

A promising minor league pitcher, John Bender had been banned from baseball for getting into a fight with his manager and stabbing him. Sorry for what he’d done, he worked like a dog for years under poor conditions to regain the respect of the players, and earned his way back into the starting rotation only to die of heart failure while on the mound pitching for the Edmonton, Alberta team. I think that Charles’s historic, almost super-human feat was a non-verbal honor song for his fallen brother, John.

In 1913, the A’s other veteran starters were injured, so Bender pioneered in the art of relief pitching to help the subs out, a science still in its infancy then. He won 21 games, six of those out of the bullpen, marking up 13 saves and losing only ten. The 34 victories he contributed to helped the A’s to the pennant in a tight three way race. Bender won two World Series games that year against the Giants, who went down in five. To give you a rough idea of how unusual relief pitching was in those days, of the 112 starting pitchers in all 56 of the World Series games played up to that point in history, a total of only 33 had needed relief pitchers. Bender was a starter again in the Series, but fortunately, the A’s didn’t need any relief, winning in five games. (The use of relievers, like the slider, didn’t really become popular until the 1940’s.)

In 1914, Bender had another great year, and pitched in the World Series against the "Miracle" Boston Braves, but the A’s were swept in four games. It turned out to be his last year in the American League. Earlier that same year, another nineteen-year old minor league fastballer soundly defeated the A’s in an exhibition game. His name was Babe Ruth. Naturally, Ruth was compared to Bender, who was discovered by Connie Mack the same way when he defeated the Cubs. Mack was almost as impressed with Ruth as he had been with Bender, but felt he couldn’t afford the price tag. A pitching fanatic, Mack’s choice to "pass" on Ruth was a turning point in baseball history, and for the A’s. If Ruth had been hired and brought in enough money, Mack would probably have been able to keep Bender and most of the other team members and extended their dynasty a while longer. However, he never would have given Ruth a chance to hit homers, or let him play the outfield. Without Babe’s "drawing card" 58 homers as an outfielder, baseball might have fallen apart after the 1919 Black Sox scandal.

Bender pitched the only American League win in the first regulation World Series, a masterful 4 hit shutout over the famed McGinnity of the Giants (who’d pitched an all-time high 434 innings in 1903). His record of pitching 20 strikeouts in the 1911 World Series was unbroken until 1945, when Newhauser hurled 22 for Detroit, but this was in a full seven game series. (Bender’s six game record still stands as far as I know.) Interestingly, Bender pitched against the Giants in the 1913 World Series, the year that Jim Thorpe played outfield for the Giants, but Thorpe never appeared at the plate. Apparently he had other things to do... like professional football.

Bender became an oil painter and lived until 1954, just long enough to see his entry into the Hall of Fame in 1953.

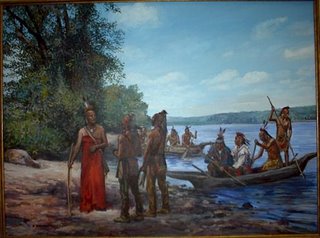

Black Hawk (Sac and Fox). When a "fly-by-night" treaty in the 1830s (see Keokuk) gave away virtually all the Sac and Fox land, Black Hawk claimed the treaty was invalid, and in 1832, led a full-scale war against President Jackson called Black Hawk’s War. After his capture, Black Hawk was taken to Washington D.C. where he met with Andrew Jackson in person, all of which made good material for his book, Autobiography of Black Hawk, which became a literary classic in the mid 1800s.

The following biographic sketch was posted on line at www.madison.k12.wi.us.

The man known to whites as Black Hawk was born Ma-ka-tai-me-she-kia-kiak (Black Sparrow Hawk) in the year 1767. Like most of the boys in his tribe, he learned to hunt and fish at an early age.

By the age of fifteen, Black Hawk had become a "brave." To become a "brave" he needed to kill or injure an enemy in battle. It was in later fighting with the Osage Indians that he earned the title of war chief. By the age of forty-five, he had killed thirty of this enemy's warriors.

Black Hawk was strong and independent minded. As a young man, he recognized the dangers of alcohol and decided never to drink the "fire water." He went against another Sauk custom of marrying more than one woman. Black Hawk married young and remained loyal to his wife, Asshewaqua (Singing Bird) throughout his life. Most successful warriors married several women.

In religion and war Black Hawk was a traditional Sauk. He rejected Christianity and continued to practice their ancient religion. Fighting was very important to the Sauk, and the warriors were ever-ready for battle. They relied on the Great Spirit to give them direction in war.

By the end of the 1700s, the Sauk were coming into contact with more and more white settlers and traders. The Sauk decided that for their own protection they would sign the Treaty of Greenville in 1795. It promised that the Sauk would be received with friendship and given protection by the United States.

In 1804, after a fight between whites and Sauk ended in the deaths of three settlers, some Sauk leaders agreed to travel to St. Louis and arrange a permanent peace. The Sauk leaders were given alcohol and asked to sign a treaty. The treaty gave the government fifteen million acres of Sauk land in Illinois, Wisconsin and Missouri for the sum of $2,274.50.

Black Hawk and other Sauk chiefs argued that the treaty was not valid because most of the Sauk Nation was not told of the treaty, and those who signed did not represent them. The government insisted the treaty was binding.

Tensions grew between the two sides until, in 1808, the Americans built a fort in the disputed territory. Black Hawk lead a war party to destroy the fort and massacre the troops but withdrew when confronted with loaded cannons.

Three years later the war of 1812 erupted between Great Britain and the United States. Black Hawk who had remained friendly to the English decided to fight on their side. Another broken promise by America strengthened his decision. The Americans said they would furnish the Sauk with supplies to help them survive. No supplies were ever sent by the government.

Saying " I have fought the Big Knives and will continue to fight them till they are off our lands," Black Hawk went on attacking the Americans even after the war with Britain was over. Finally a treaty was signed to bring about a temporary peace.

By 1821 lead mining brought floods of white settlers to northwestern Illinois and southwestern Wisconsin. By 1828 the Sauk and the Fox tribes were forced from their lands and driven across the Mississippi River. In the spring after a snub by President Andrew Jackson, Black Hawk decided to return across the river and reclaim his land. In 1832 Black Hawk was invited to live in a village of Winnebago Indians led by his good friend White Cloud. Crossing the Mississippi with 400 braves and their families, Black Hawk caused mass hysteria. Although Black Hawk and his braves bothered no one, Governor John Reynolds called out the Militia. Among the 1600 men who volunteered to fight was a young lawyer named Abraham Lincoln.

The Winnebagos and other tribes in the area, fearing the militia, refused to let Black Hawk stay. Reluctantly, he decided to swallow his pride and return to Iowa.

Meanwhile, the militia was approaching. Black Hawk sent five warriors to tell the militia that his people wanted to peacefully retreat across the Mississippi. All of the warriors were immediately taken prisoner. Black Hawk sent more warriors to see what happened. They were attacked and two warriors were killed. The militia set out after the rest of Black Hawk's people. They were ambushed by Black Hawk and forty of his braves. Eleven of the militia and three of the warriors were killed before the militia broke and ran.

The war had begun. Winnebago and Potawatomi warriors joined Black Hawk and the raided villages and farms through northern Illinois and southern Wisconsin. At Ottawa, Illinois, they shot, tomahawked and mutilated the bodies of fifteen settlers and kidnaped two teenaged girls. ( The girls were later released ). These attacks created widespread panic among the white settlers and thousands fled the area.

Black Hawk was still trying to get across the Mississippi. He decided to travel through the Wisconsin wilderness. To cover his retreat he sent out war parties to attack white settlements hoping to delay the pursuing soldiers.

On July 21, 1832, the troops finally caught up with Black Hawk's rear guard near present-day Sauk City, Wisconsin. The ensuing battle ( The Battle of Wisconsin Heights ) cost the lives of five warriors and one soldier. The soldiers leery of an ambush let the Sauk slip away an escape.

Black Hawks only hope lay in out running the soldiers and he raced to the Mississippi. When he arrived at the river he found his way blocked by an American steamship loaded with troops and artillery. Black Hawk tried to surrender and sent two warriors under a white flag to the ship. The ship's captain did not understand the request and opened fire on the Sauk. Black Hawk and his followers were trapped.

The next day, August 2, 1832, the soldiers caught up with the Sauk. In what became known as the Bad Axe Massacre, the soldiers killed dozens of the Sauk including women, children and the elderly. Those who made it across the Mississippi were killed by the Sioux, who had joined the Americans. Of the 500 Sauk with Black Hawk, only about 150 survived. The Black Hawk war, now virtually over, had cost the lives of 72 whites and between 450 and 600 Native Americans.

Black Hawk was one of the survivors. He was eventually forced to surrender with his friend, White Cloud, of the Winnebago's. The were sent to the east and were paraded through the eastern cities like captured animals. The public , however, greeted him, "as a brave, romantic symbol of the wild frontier and treated him like a hero.

Black Hawk later was returned to Iowa. In the last few months of his life he found himself the object of admiration among Iowa settlers. He was often invited to the territorial capital to attend sessions of the legislature. His last public appearance was July 4, 1837.

Black Hawk died in his lodge on October 3, 1837. His wife Singing Bird survived him. In his last public appearance he said: " A few summers ago, I was fighting against you. I did wrong, perhaps, but that is past. It is buried. Let it be forgotten. Rock river was beautiful country. I loved my towns, my cornfields, and the home of my people. It is yours now. Keep it as we did."

Written by - Chuck Pitcel

Black Kettle (Southern Cheyenne). Born in 1803, Black Kettle became one of the famous "Dog Soldiers" as a young man. As chief, his band was constantly attacked by U.S. soldiers, but he was a man of peace and never gave up trying to negotiate. He was known for stopping young warriors from raiding white settlements, and for risking his life to return white captives to their families. Even after two hundred of his band were massacred, Chief Black Kettle continued to attend treaty councils.

His people were promised a large parcel of land lying between western Kansas and eastern Colorado in the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851, one of the more infamous treaties ever penned.

Black Kettle had been living in this territory his whole life. In that treaty, signed by the Cheyenne, Lakota, Crow, and other tribes, the U.S. promised to pay each tribe $50,000 per tribe for fifty years. The agents who negotiated the deal for the U.S. couldn’t support the terms of the treaty, but the Cheyenne, Lakota, and Crow didn’t know that, and ended up not receiving the money they were promised.

In 1859, gold was found at Pike’s Peak in Colorado, triggering a massive gold rush not unlike the one ten years earlier in California, and great masses of white men, some crazed with the lust for gold, invaded the territory and drove off the native people. For two years, Black Kettle’s people wandered homeless around the territory which had been given to them. Finally, in 1861, he signed a new treaty for a smaller piece of land called the Sand Creek Reservation.

It was a sparse terrain, and within a year there weren’t enough buffalo to provide food and clothing for the people. They began to travel up to 200 miles to find a buffalo. In desperation,

the rogue Indians among them began killing the squatters’ livestock for food.

In 1864, Black Kettle returned to the reserve to restore the peace between the settlers and the Cheyenne. Colonel John Chivington and his men attacked the camp, killing anyone in their way and sexually mutilating the dead women. Chief Black Kettle and his wife barely escaped with their lives.

Black Kettle and his wife were finally killed by Custer’s 7th Cavalry on November 27, 1868. This was in spite of the fact that the Chief had a white flag flying in plain sight over his teepee, and in spite of his life-long peace-keeping efforts, and his efforts to save the lives of white settlers during his sixty-five years of life. Custer’s cavalrymen shot the great Chief and his wife many times, and continued to shoot their bodies full of bullets long after they were dead. Black Kettle’s story is told at length in Bury My Heart At Wounded Knee, by Dee Brown.

The following is from the PBS website The West: Black Kettle lived on the vast territory in western Kansas and eastern Colorado that had been guaranteed to the Cheyenne under the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851. Within less than a decade, however, the 1859 Pikes Peak gold rush sparked an enormous population boom in Colorado, and this led to extensive white encroachments on Cheyenne land. Even the U.S. Indian Commissioner admitted that "We have substantially taken possession of the country and deprived the Indians of their accustomed means of support."

Rather than evict white settlers, the government sought to resolve the situation by demanding that the Southern Cheyenne sign a new treaty ceding all their lands save the small Sand Creek reservation in southeastern Colorado. Black Kettle, fearing that overwhelming U.S. military power might result in an even less favorable settlement, agreed to the treaty in 1861 and did what he could to see that the Cheyenne obeyed its provisions.

As it turned out, however, the Sand Creek reservation could not sustain the Indians forced to live there. All but unfit for agriculture, the barren tract of land was little more than a breeding ground for epidemic diseases which soon swept through the Cheyenne encampments. By 1862 the nearest herd of buffalo was over two hundred miles away. Many Cheyennes, especially young men, began to leave the reservation to prey upon the livestock and goods of nearby settlers and passing wagon trains. One such raid in the spring of 1864 so angered white Coloradans that they dispatched their militia, which opened fire on the first band of Cheyenne they happened to meet. None of the Indians in this band had participated in the raid, however, and their leader was actually approaching the militia for a parlay when the shooting began.

This incident touched off an uncoordinated Indian uprising across the Great Plains, as Indian peoples from the Comanche in the South to the Lakota in the North took advantage of the army's involvement in the Civil War by striking back at those who had encroached upon their lands. Black Kettle, however, understood white military supremacy too well to support the cause of war. He spoke with the local military commander at Fort Weld in Colorado and believed he had secured a promise of safety in exchange for leading his band back to the Sand Creek reservation.

But Colonel John Chivington, leader of the Third Colorado Volunteers, had no intention of honoring such a promise. His troops had been unsuccessful in finding a Cheyenne band to fight, so when he learned that Black Kettle had returned to Sand Creek, he attacked the unsuspecting encampment at dawn on November 29, 1864. Some two hundred Cheyenne died in the ensuing massacre, many of them women and children, and after the slaughter, Chivington's men sexually mutilated and scalped many of the dead, later exhibiting their trophies to cheering crowds in Denver.

Black Kettle miraculously escaped harm at the Sand Creek Massacre, even when he returned to rescue his seriously injured wife. And perhaps more miraculously, he continued to counsel peace when the Cheyenne attempted to strike back with isolated raids on wagon trains and nearby ranches. By October 1865, he and other Indian leaders had arranged an uneasy truce on the plains, signing a new treaty that exchanged the Sand Creek reservation for reservations in southwestern Kansas but deprived the Cheyenne of access to most of their coveted Kansas hunting grounds.

Only a part of the Southern Cheyenne nation followed Black Kettle and the others to these new reservations. Some instead headed north to join the Northern Cheyenne in Lakota territory. Many simply ignored the treaty and continued to range over their ancestral lands. This latter group, consisting mainly of young warriors allied with a Cheyenne war chief named Roman Nose, angered the government by their refusal to obey a treaty they had not signed, and General William Tecumseh Sherman launched a campaign to force them onto their assigned lands. Roman Nose and his followers struck back furiously, and the resulting standoff halted all traffic across western Kansas for a time.

At this point, government negotiators sought to move the Cheyenne once again, this time onto two smaller reservations in Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma) where they would receive annual provisions of food and supplies. Black Kettle was again among the chiefs who signed this treaty, the Medicine Lodge Treaty of 1867, but after his people had settled on their new reservation, they did not receive the provisions they had been promised, and by year's end, more and more of them were driven to join Roman Nose and his band.

In August 1868, Roman Nose led a series of raids on Kansas farms that provoked another full-scale military response. Under General Philip Sheridan, three columns of troops converged to launch a winter campaign against Cheyenne encampments, with the Seventh Cavalry commanded by George Armstrong Custer selected to take the lead. Setting out in a snowstorm, Custer followed the tracks of a small raiding party to a Cheyenne village on the Washita River, where he ordered an attack at dawn.

It was Black Kettle's village, well within the boundaries of the Cheyenne reservation and with a white flag flying above the chief's own tipi. Nonetheless, on November 27, 1868, nearly four years to the day after Sand Creek, Custer's troops charged, and this time Black Kettle could not escape: "Both the chief and his wife fell at the river bank riddled with bullets," one witness reported, "the soldiers rode right over Black Kettle and his wife and their horse as they lay dead on the ground, and their bodies were all splashed with mud by the charging soldiers." Custer later reported that an Osage guide took Black Kettle's scalp.

On the Washita, the Cheyenne's hopes of sustaining themselves as an independent people died as well; by 1869, they had been driven from the plains and confined to reservations.

Blue Jacket (Shawnee). Blue Jacket was one of the Shawnee chiefs temporarily allied under Tecumseh. A child of white settlers, he was born in Virginia as Marmaduke Van Swearingen, then captured at seventeen and adopted into the Shawnee as Wehyehpihehrsehnwah. He came fully Shawnee, but not before undergoing considerable initiation, including "running the gauntlet," having his whole body painted and then scrubbed with sand, and worst of all perhaps, learning to pronounce his name. Finally, he was brought into the msi-kha-miqui house, and all the people gathered. He was painted yet again, and Chief Pucksinwah put his hand on the boy’s shoulders and said, according to Eckert’s realization, "My son, you are now flesh of our flesh. By the ceremony performed this day, every drop of white blood is washed out of your veins. You are taken into the Shawnee Nation and initiated into a warrior sept. You are adopted into a great family and received with great seriousness and solemnity... After what has passed this day, you are now one of us by an old strong law and custom."

In 1790, Blue Jacket, accompanied by Little Turtle of the Miami, ambushed and defeated a mixed force of U.S. Army regulars and militiamen who were in the Native American region now known as Ohio. (The Treaty of 1763 promised Ohio to the natives. But then there was the Jay Treaty, and things were not clear as to who was where.) This action drew the popular General Arthur St. Clair and 2,300 militiamen into the Ohio region to retaliate. Not unlike the Battle of the Little Bighorn, St. Clair’s last stand was an historic setback for the United States, which had just won the war with Britain. His army soundly out-fought, St. Clair, himself seriously wounded and over six hundred of his men killed, including many officers, they retreated to the colonies. This battle halted white migration westward. Later, President Washington would send "Mad Anthony" Wayne to the northwest territory with a new larger group of men, to subdue the natives by any means necessary, which is exactly what Wayne had in mind.

Realizing the grim resolve of the new army, Little Turtle counseled for peace and kept his Miami forces out of battle. It saved the Miami from destruction at the disastrous Battle of Fallen Timbers where Blue Jacket was defeated and forced to retreat. General Wayne followed his footsteps, burning and destroying native villages in his wake.

A former friend of Tecumseh, Blue Jacket was one of many chiefs who signed the Treaty of Greenville in 1795, setting up a new boundary further west between white settlements and native settlements. Greenville undermined Tecumseh’s efforts for a Native American union in the Ohio valley. However, Tecumseh regrouped, and staged a considerable comeback culminating in the War of 1812, which marked the defeat of the Tecumseh nation.

The following is from ohiohistorycentral.org: Blue Jacket was a chief of the Shawnee Indians. The date of his birth is unknown, but it was probably in the early 1740s. His Native American name was Weyapiersenwah (also spelled Wehyehpiherhsehnwah). Historians know very little of his early years. In 1774, Blue Jacket participated in Lord Dunmore's War. In this conflict, militiamen from Pennsylvania and Virginia hope to force the Ohio Country natives to accept the Treaty of Fort Stanwix (1768). The major battle in this war was the Battle of Point Pleasant. The English succeeded in defeating a force of Shawnee Indians led by Chief Cornstalk. Blue Jacket participated in the battle. During the American Revolution, Blue Jacket, as did most Shawnees, sided with the British. By the war's conclusion, Blue Jacket had settled along the Maumee River.

During the early 1790s, Blue Jacket and Chief Little Turtle of the Miami Indians were the major leaders of the natives in the Ohio Country. They led their braves against American settlers in western Ohio as the whites swept into the area. The natives defeated an army led by General Josiah Harmar in 1790 and another one led by Arthur St. Clair in 1791. St. Clair's Defeat was one of the worst defeats for the American military at the hands of the Indians. Following St. Clair's Defeat, Little Turtle called for negotiations between the Indians and the Americans. The natives' British ally had failed to support the Indians fully during the past several years against the Americans. Little Turtle believed that, without England's help, the natives had no serious chance against the Americans. Blue Jacket then assumed control over native attempts to stop the influx of settlers. In 1794, he led the Native Americans against an army led by Anthony Wayne. The two sides met at the Battle of Fallen Timbers. Wayne emerged from the battle victorious. Blue Jacket's men fell back to Fort Miamis, a British stronghold. The British refused to assist the natives, and Blue Jacket and his followers agreed to negotiate with the Americans.

In 1795, the Shawnees, represented by Blue Jacket, signed the Treaty of Greenville. The natives agreed to relinquish all claims to land in Ohio except for the northwestern corner. In 1805, Blue Jacket also signed the Treaty of Fort Industry. Under this agreement, many Ohio Country natives agreed to cede parts of northwest Ohio to the United States.Blue Jacket died circa 1810. He probably resided near Detroit.

Ignatia Broker (Ojibway). Born on Valentine’s Day, 1919 at Pine Point on the White Earth Indian Reservation, Broker was a member of the Ottertail Pillager Band of Ojibways, Awasasi Clan. Starting out as a journalist for the Minneapolis Star Tribune immediately after World War II, she became a pioneer in Native American literature in a time and place of great hostility towards the Ojibway. She began a new career at the age of forty-seven with the Minneapolis Public Schools in 1966, and helped develop the Title IV Indian Studies Curriculum, authoring many stories, film strips, and booklets that are still part of the curriculum today.

She founded the Minnesota American Indian Historical Society, and worked for countless other organizations, receiving one of fourteen national awards given by the Wonder Woman Foundation in 1984. Her only novel, Night Flying Woman: An Ojibway Narrative, a novel about her great-great-grandmother Oona, which she begun writing in 1969, was not published until 1983. Ignatia died of lung cancer on June 23, 1987. (From the Internet site “Ojibway Role Models.”)

Archie Cheechoo: (Cree) Archie Cheechoo, whose debut CD "Bay Life" paints pictures of life on the shores of James Bay and has earned great reviews. Archie Cheechoo was a great help to me and my family as a spiritual advisor and friend, and shared stories of his amazing family with ours. Archie Cheechoo passed away on February 17th, 2006 . His teachings were quoted in No Word For Time, Native New Yorkers, and elsewhere.

Mrs. Calvin Coolidge aka Grace Anna Goodhue (Wampanoag?).

Mrs. Calvin Coolidge aka Grace Anna Goodhue (Wampanoag?). Grace married Calvin in 1905 and got to live in the White House, but according to one source, even as First Lady she was snubbed by Washington society. She was born in 1879 and died in 1957 (during my lifetime!). They had two children. Calvin Coolidge was from Vermont, but had a life-long fascination with Native Americans, and was not totally hush-hush about it. At least once he had a large delegation from the Sioux nation at the White House, and was a champion of native land interests. Interestingly, the nation’s fortunes prospered as never before while Coolidge (and his wife) was in office. Together they served six years. That she was a "New England Indian" I have on grapevine status, however I have not seen it in the written records.

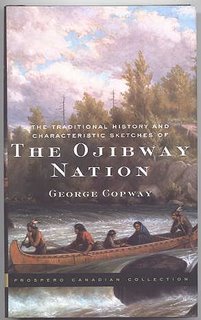

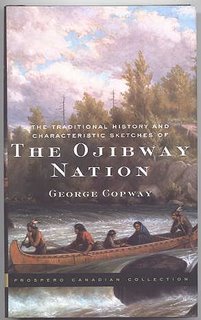

George Copway aka Kahgegagahbowh (Ojibway).

George Copway aka Kahgegagahbowh (Ojibway). Copway was born in 1818. He wrote The Life, History and Travels of Kahgegagahbowh and Young Indian Chief of the Ojebwa Nation, published in 1847, at the age of twenty-nine, and several other books followed. He died in 1869.

George Crum (Mohican/Huron). There seems to be some dispute over which group of indigenous people Lays the best claim to cooking up the first potato chip. But I have been told that the creator of one of my favorite foods (and potatoes were definitely the invention of the Native American) was at least part Mohican. He was a "chief," chief cook at a resort hotel called Moon Lake House in Saratoga Springs, New York.

One of the more fussy guests, supposedly a certain Mr. Cornelius Vanderbilt, ordered a new dish called French Fried Potatoes. When Crum brought it out, Vanderbilt sent it back saying it was too thick. "I know how it’s supposed to be prepared, because I’ve been to France!" he exclaimed.

This happened several times, until George, in exasperation, cut the potatoes razor thin. Much to his surprise, Vanderbilt really liked the new variation on French Fries, and today we call them Potato Chips, and we also eat them, apparently. In 1972, total sales reached the $1 billion mark.

Chief Dark Cloud (Algonquin). A movie actor, Chief Dark Cloud played in some significant silent film roles, specifically “Intolerance” (1916) and several with D.W. Griffith

in 1911.

Beulah Dark Cloud (Algonquin). Daughter of the above, she was involved in films and lecturing on Native American issues until her death in 1946. She was highly committed to American Indian organizations in Los Angeles.

Nora Thompson Dean aka Touching Leaves (Unami Delaware).

Nora Thompson Dean aka Touching Leaves (Unami Delaware). Nora was one of the principle preservers of Lenape culture and language in the 20th Century. I became interested in Lenape ways just about the time she passed away, and it was by listening to several taped interviews of her lectures that I got my first taste of Lenape lifeways and phrases.

Joseph F. Dion (Cree).

Joseph F. Dion (Cree). Dion, born in 1888, was a farmer, school teacher, writer and important political leader among Cree and Metis people. He wrote My Tribe, The Crees, which was published after his death in 1960.

Dull Knife (Cheyenne).

Dull Knife (Cheyenne). He fought alongside the Sioux during the battles for the Black Hills in the 1870s. He and Little Wolf were there when the Sioux and Cheyenne together defeated Custer’s Seventh Cavalry at the Little Big Horn.

Captain Grey Eyes (Lenape). See White Eyes

Hendrick (Mohawk/Mohican).

Hendrick (Mohawk/Mohican). Although Hendrick was a famed Mohawk Chief, there is documentation that he was part Mohican as well. He allied himself with the British and even visited England in 1710, where he was presented to Queen Anne as "King of the Mohawks." At the age of seventy, Hendrick went to war with the British against the French, and was killed at the Battle of Lake George in 1755.

Langston Hughes (Pamunkey/African-American/Osage).

Langston Hughes (Pamunkey/African-American/Osage). Although Langston Hughes was absorbed most of his life with African-American culture, both sides of his family were from prominent southern Native American lineages, primarily the Pamunkey of Virginia (who are Algonkeean), and the Osage of his native Missouri (a Siouxian people).

Hughes was born February 1, 1902 in Joplin, Missouri, the son of abolitionist parents. He was the grandson of James Mercer Langston, the first "black American" to be elected to public office in 1855 (also of mixed Native American heritage). Langston discovered poetry at an early age and was class poet in the eighth grade. His father paid for him to pursue an engineering degree at Columbia, which he attempted, and earned a B+ average. However, he eventually got restless and dropped out to devote himself to poetry. The rest of his life he emphasized individual freedom and being true to oneself, although he never acknowledged his native self in public.

Langston loved jazz and blues and listened to a lot of it, both in the U.S. and abroad. When he returned to Harlem in 1924 after extended travels, he became part of the Harlem Renaissance and was widely published. In 1925, he moved to Washington, D.C., but returned to Harlem late in 1926. He created a character called My Simple Minded Friend after a man he knew from a bar in Harlem. In 1950 he renamed this person Jess B. Simple, and wrote a series of books on him.

Langston Hughes wrote steadily for forty years, mostly about the black experience in America. He wrote sixteen books of poems, two novels, three collections of short stories,

four volumes of editorial fiction, twenty plays, three autobiographies, a dozen radio and

television scripts, and works for children. He even wrote musicals and operettas.

Hughes died of cancer on May 22, 1967. His home at 20 East 127th Street in Harlem,

New York City, is now a landmark. The street was renamed Langston Hughes Place in his honor.

Mali Keating (Abenaki). Ms. Keating was an outspoken advocate

for preservation of Algonkeean culture, and is on the Wabenaki Confederacy Council. She was elder-in-residence at Dartmouth College in New Hampshire, and was involved with Abenaki self-government and also the Three Fires Midewiwin society. Among many reasons, I honor her for gifting me with traditional Algonkeean medicine (tchee-choss or tree medicine) to cure a migrain headache. She lives in Vermont.

Maude Kegg aka Naawakamigookwe/Middle Earth Lady (Ojibway).

Maude Kegg aka Naawakamigookwe/Middle Earth Lady (Ojibway). Best known as a writer, her books are bilingual, written as she speaks them in Ojibway, then translated into English by John D. Nichols. She was born in a birchbark wigwam near a wild rice harvesting camp in Crow Wing County, Minnesota in 1904, around August 26th. Kegg’s mother’s family members were among two hundred and eighty-four of the Chippewa band that refused to relocate to the White Earth Reservation because it was a breach of treaty. They fought for tribal recognition for thirty years, and in 1934 finally won the rights to their own reservation. Maude attended the public school, as the only person of color, until the eighth grade. She married Martin Kegg in 1920 and raised ten children. Kegg worked as an artist, worked outdoors, and during the last thirty years of her life on the Mille Lacs Reservation, acted as mentor to John D. Nichols, who learned much about Ojibway linguistics and history from her. She was also an interpreter of Ojibway culture at the Minnesota Historical Society Museum. August 26, 1986 was declared Maude Kegg Day and in 1990 President George Bush presented her with the National Heritage Fellowship Award. Her best known book is Portage Lake, about her childhood. Another book, What My Grandmother Told Me, deals with more adult-oriented issues. She passed away

January 6, 1996 at age ninety-one.

Keokuk (Sauk).

Keokuk (Sauk). Keokuk was so courageous in a difficult battle with the Sioux that he was named Chief of the Sauk. Later, many of Keokuk’s people considered him a traitor for capitulating to the demands of the U.S. Government to divide their lands and denounced him.

He refused to resign. Black Hawk, considered the legitimate chief according to tradition, defied the treaties and led his followers against Keokuk and the American forces. This war escalated and many lives were lost. In the end, the American army won the war which is now remembered as "Black Hawk’s War." Keokuk died in 1848.

Albert Lightning (Cree).

Albert Lightning (Cree). For many decades Albert Lightning was the recognized Medicine Chief for a large portion of Algonquian-speaking people. He was also the founder and publisher of The Cree News, a highly successful newspaper. Large crowds flocked to hear him speak whenever he appeared. I heard his teachings through his assistant Grandfather Turtle, and developed a deep interest in this legendary elder who lived in the high northern Rockies. Those Canadian Rockies are to many Algonkeean people what the Himalayas are to many Asian Indians, and he was the ancient sage who, like the Masters of the Himalayas, held power in the thoughts and dreams of an entire people. He was an inspiration to thousands until his death at the age of ninety-four.

Although I never met Albert Lightning, I was walking in the woods one day with my infant son, and a tall, impressive-looking full-blooded Native American man walked by with his boy who was playing with a blue ball. Uncharacteristically, my little boy took the ball away from the other boy, and I had to step in and apologize to the seven-foot tall "warrior" (or so he looked to me) and hand him the ball. This led to a conversation in which I quickly learned the crushing news of Albert Lightning’s passing two days after the funeral. The man, whose name was Franco, another great Algunkeean, had just come directly from the ceremony, two thousand miles away, and was on his way further eastward. Our meeting was, as they say "mere coincidence."

The following was published online at albertasource.ca “Albert Lightning was a revered old Cree ceremonialist and medicine person from the Ermineskin band in Hobbema. He was a favourite guest at spiritual and official gatherings. Meli followed his career and reports the following:

He spoke of natural law and how the truth will never lead anyone astray, but individuals must be strong enough to hold on to their good decisions. People must not look for physical or material results from everything they do. Instead, they should pay attention to their dreams and develop their spirits, feeling good about helping others and putting themselves last. They must see what is real in life, not the unreal. I remember Albert nodding in agreement with Chief John Snow’s words to the crowd: “Although people think the grandfathers have abandoned us, what with all the bad things that have been going on in the Indian world, these spirits have always been with us. It is we who have forgotten about them.” Albert made it clear he wanted to share his knowledge of the spiritual undercurrents in everyday life with conference delegates and invited them into his magnificently painted tipi to see black-and-white, poster-sized photographs of spiritual images he had collected. One, taken at the top of a mountain in the Kootenay Plains area of the western Rockies, showed the distinct form of what looked like a veiled figure standing out in white against a gray, cloudy sky.

"I show these pictures because so many people need to see proof before they will believe. I show them so people might come closer to believing the spirit world and that the Creator looks out for us," he told the group.

Albert talked a lot about natural law. He said that humans’ inner natures are an exact copy of the nature of the universe, and deep knowledge of the self comes from nature. Western society’s materialism and technology is unnatural to the point that many people are unaware of natural cycles and energies and even fear insects, animals, trees, and birds. As humans become unbalanced, so does their world. Medicine people understand natural laws and work with varying frequencies of energy to accomplish what seems impossible. They know there is a right time and place for everything and what is possible given a certain set of circumstances. They know when to pick herbs and not to waste anything, because waste is unnatural. (Meili, 82f.)

Harry Lincoln (Meskwaki). Lincoln translated the Meskwaki text "How Meskwaki Children Should Be Brought Up," into the English language at the turn of the century. It was then written down by Truman Michelson and published in American Indian Life, in 1922.

Chief Edward Little (Chippewa) was a silent film actor, who lived from 1868 to 1928.

Little Turtle (Miami).

Little Turtle (Miami). Adopted into the Miami Nation as a youth, he was born in 1752 in the Illinois country. Miami war chief Little Turtle fought alongside Tecumseh’s father Punksiweh and later Tecumseh himself in holding the English settlers east of the Ohio.

He defeated U.S. General Josiah Harmar on the Miami River in 1791. Later in 1791, he led a Great Lakes Tribal Confederacy against General Arthur St. Clair. The Confederacy killed six hundred and twenty-three soldiers and lost only twenty-one, but were defeated at Fallen Timbers in 1794. They retreated as planned to the British fort, but were locked out and destroyed.

Little Turtle survived, and in 1797 he met with President George Washington and became an ally of the Americans. He was a moderate dedicated to neutrality whenever possible. He refused to fight with Blue Jacket at the disastrous battle of Fallen Timbers, or with Tecumseh during the Tecumseh’s wars against the whites. He died in Fort Wayne, Indiana in 1812.

Little Wolf (Cheyenne)

Little Wolf (Cheyenne) fought alongside the Sioux during the battles for the Black Hills in the 1870s. He and Dull Knife were there when the Sioux and Cheyenne together defeated Custer’s Seventh Cavalry at the Little Big Horn.

Massasoit (Massachusett/Pocanoket)

Massasoit (Massachusett/Pocanoket) befriended colonists of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, teaching them how to plant corn, and how to protect themselves from warring tribes. He also acted as their patron saint and step-father, actively preserving a haven of peace for them for over ten years. As the colonists grew in numbers, they soon overran the agreed-upon boundaries and broke their treaties with their benefactor. Soon, neighboring tribes had had all they could stand of this lenient stance, and it resulted eventually in King Phillip’s War. It was Massasoit’s own son Metacomet who unified the Algonkeeans and led the charge to avenge the cruelties of the Plymouth Colony, including possibly the murder of his older brother.

Henri Membertou (Micmac).

Henri Membertou (Micmac). A grand chief of the Micmac, it was said Membertou would always go half way to negotiate peace. When the Catholic Missionaries were trying to take over, he negotiated with Rome and established what later became known as The Church of Membertou. Even to this day, all services are conducted in Micmac, without emphasis on books, and usually out of doors. It was one of the first successful missions in the New World, and with the help of the French Catholics and their powerful church, the Micmacs were able to preserve their language and much of their indigenous culture to this day. Even though surrounded by urban centers, at least 10,000 Micmacs today still speak their language, 5,000 of these attending the church, which has been recognized by every Pope since the 1500s.

Membertou, born in 1505, was already an ancient chief of the Micmac of the western valley by the time Pierre de Mont and Samuel de Champlain arrived and built the first French settlement in North America in 1604. This settlement was at the St. Croix River which today is on the U.S. Canadian border, between New Brunswick and Maine. The French had a rough winter and moved to a new location called Port Royal, which was located in Membertou’s Micmac territory. When younger, Membertou had been a famed war chief. Now at the age of 100, he was a man of peace. Membertou formed strong alliances with these new French settlers and created highly successful trade networks with them, which would become a dominant economic power in the northeast only a few years later. Trappers and traders of all nations would have to learn "Trade Micmac" language in order to succeed.

Membertou was open-minded to the early teachings of the Jesuit missionaries and in 1610, he and his family were among the first converts, although on the condition that all Micmac traditions would forever be respected. Many of his kinsmen followed suit. The following year,

a major epidemic broke out, and at the age of 107, Membertou succumbed to the disease and died on September 18th, 1611.

Micmac is one of the more widely spoken Algonkeean languages today. By insisting that the church take responsibility for helping to preserve it, Membertou helped to insure the popularity of the Micmac language.

Metacom aka Metacomet (Wampanoag).

Metacom aka Metacomet (Wampanoag). The son of Massasoit, a sachem who was friendly to the whites, Metacomet resisted Puritan land seizures and taxes after he became chief in 1662

at the age of twenty-four. He felt that the colonists would eventually bring the extermination of all his people, and formed an army to attack the settlers. He managed to cripple or destroy most of the white settlements of Massachusetts and Rhode Island. His 500 men were soon joined by 20,000 warriors from neighboring tribes, mostly Nipmuc, and their rebellion was called "Prince Philip’s War." The result was an Algunkeean Federation, but due to pressure from English troops which eventually numbered 50,000, and with the help of the Mohegan, the Federation was weakened.

In 1676, King Philip was defeated and most of his people killed or sold into slavery and shipped to the Bahamas. The descendants of the Wampanoags and Pequots are still on St. Croix today, speaking their language and still recanting their long history. Their settlement is on the western shore of St. Croix Island, several miles northwest of Christiansted and facing the island of Vieques to the north.

William Mewer (Micmac). In 1891, at the age of twenty-eight, William Muse covered his Micmac tracks and immigrated to the United States, changing his name to Mewer. He soon got a job in a sawmill, and so impressed the mill owner and his wife that he ended up marrying their daughter, Hattie, who was to become my great-grandmother. They moved to Old Orchard,Maine and as a couple became a symbol of Downeaster integrity.

Their first child, Clinton was born in 1895, and grew up to run the family businesses. Bill was an inventor, a builder (he built what we now know as Old Orchard Beach, Maine), and a pioneer in the insurance business. A friend of Teddy Roosevelt (he headed the Bullmoose party for Maine, according to his daughter Helen Perley), Bill was elected congressman, serving from 1903 to 1909, and was police chief every year after that.

Mewer distinguished himself as an architect who never used blueprints. Nevertheless, he was among the first to experiment successfully with cement and created the Old Orchard Beach Town Hall, an architectural marvel of the time. He was also a powerful mystic and 33rd degree Mason. At the same time he consistently devoted himself to the preservation of the Algonkeean people of Maine during their darkest years, 1890-1920, especially as a Congressman. He died of heart failure in January 1925 on a grim 15° below zero day at the age of sixty-two, apparently while shoveling snow.

Larry Cloud Morgan (Ojibway).

Larry Cloud Morgan (Ojibway). Confined to a wheelchair for many years, Larry passed away in 1999, but first was able to pass on much of his linguistic knowledge to the younger people of his Ojibway nation, and to linguists at Harvard and other prominent universities around the country. I had a pleasant chat with him in Washington D.C. at the Prayer Vigil in front of the White House in 1998.

Chief Francis Joseph Neptune (Passamaquoddy) is a famous name in Algonkeean history. A portrait of his daughter Denny Sockabasin was made in 1817. There were a long line

of Neptunes who maintained some of the Midewiwin traditions long after the Lodge Chiefs went west.

Nesouaquoit (Fox).

Nesouaquoit (Fox). Son of Chief Chimakassee of the Fox, Nesouaqouit became chief after his father. Like most Fox leaders, he was of the bear clan. He visited Washington, D.C. with Keokuk and Black Hawk in 1833 to meet President Andrew Jackson.

Netawatwees (Lenape). This influential nonagenarian at the time of the Declaration of Independence became head of the Delaware Great Council at a critical time in their history. He invited the help of the Moravian Missionaries, and allowed them to be honorary Delaware.

In return, they acted as effective scribes and messengers to speed up interaction between the Delawares and the Continental Congress. As the American Revolution developed, Congress used these communication lines to convince the native population that the British would lose the war, and to win their support.

Netawatwees also founded the town of Newcomerstown, Ohio in 1771, and it became the largest settlement of non-Christians in the New World. He lived there himself, in a two-story log cabin, with a staircase and a stone chimney, and made it the capital city of the Delaware for a period of time. By 1776, the population exceeded 700.

Netawatwees was of the Unami or Turtle Nation of the Delaware Confederacy, located in central New Jersey. There had always been a tendency for the grand sachem to be of the Unami, but with Netawatwees this became institutionalized, and whether the practice was ever considered "law" before, it now was because of him. Strongly associated with the Turtle, the first of all creatures in the Creation tales, Netawatwees was clearly the first of leaders above all other Lenape leaders at the time of the Revolution.

At Fort Pitt on October 31, 1776, as he lay dying, Netawatwees gave his last great speech, urging his people to heed the advice and teachings of the pacifist Moravians. White Eyes later delivered his speech to the Great Council.

If his advice had been followed, a new Pro-American Christian Delaware Commonwealth might have been born, a separate country (or state) where converted Delaware people could live in peace. In the end, there were too many who felt the move towards Christianity and American politics betrayed their own ways of life and independence. Anti-American sentiment and an understandable lack of trust of Europeans broke up the alliance. The American side won the war, and the Delaware were driven from the land, many seeking refuge in Canada, where a large group now reside today.

Daniel Ninham (Wappingers).

Daniel Ninham (Wappingers). Grand Chief of the Wappingers, Ninham fought in the Revolutionary War on the American side, and was shot while mounting his horse near the end of the war. Ninham’s life was marked by great deeds and profound sorrow and loss. He was one of the most widely respected native leaders of his time.

Also called "David Ninham," he worked to recover the lands lying along the eastern shore of the Hudson River that had been taken by the English. This resulted in a Wappingers’ reservation whose borders are now marked by the borders of modern-day Putnam County. He was made a chief in 1740, and in spite of his feelings against the English, he entered into their service in 1755 under the influence of the likable British diplomat Sir William Johnson. Ninham brought with him most of his fighting men to fight against the French. Later, in 1762, he went to England to fight for tribal land claims with a few Mohegan chiefs. The claims reached the court, but with the outbreak of the American Revolution, they were pushed aside.

Ninham fought valiantly with the Americans during the Revolution. He and seventeen Stockbridge Indians, with forty men in all, put up a desperate resistance against the British Legion Dragons in the Battle of Kingsbridge. Ninham wounded British Commander Simcoe, but was killed by Simcoe’s orderly in the process. Ninham’s Stockbridge troop were wiped out by vastly superior numbers and were buried where they fell, near Tibbet's Brook (Moshulu Seepu). There is a monument on that site which is now called "Indian Field," a plot of land in Van Cortland Park.

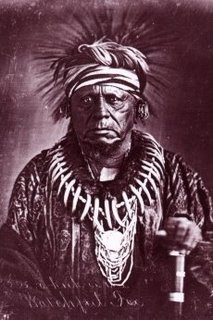

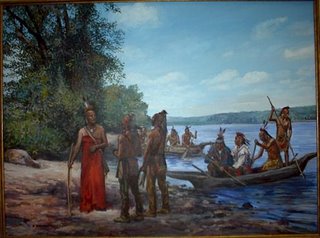

Okeemaquid (Ojibway). He was a leader among the warriors of the Chippewa/Ojibway during the wars with the Sioux in the early 1800s (Minnesota). The wars ended in 1825, and a peace treaty was signed, with gifts exchanged. He was given a feathered headdress by the Sioux, which he wore when posing for a portrait by an American artist, which helped to insure his place in the English history books.

Helen D. Perley (Micmac). Owner and operator of The White Animal Farm on Seavee Landing Road in Scarboro, Maine, "Aunt Helen" was an American institution and symbol of salty old Maine culture who exchanged letters with several U.S. Presidents. Her knowledge of animals and plants was simply phenomenal, and she was often sought after by Walt Disney and Hollywood animal trainers for her great animal knowledge and compassionate animal-human communication skills. Helen was a champion clam digger, survivalist, and herbalist. My book Aunt Helen’s Little Herb Book, preserves some of her knowledge and stories, and Bob Noonan has written two articles for Readers’ Digest about Helen’s magical ways with animals.

Pocahontas (Chickahominy/Cherokee). The daughter of Powhatan and the subject of a cartoon movie, her real name was Matoakah and she lived from 1595 to 1617. Her mother was a Cherokee named Amastayi. The nickname Pocahontas has been translated "She is frisky," "Spoiled Child," or "Naughty One." If she did rescue John Smith, she would have been ten or eleven years old at the time. This is unlikely. What probably happened is this: Pocahontas was treacherously taken prisoner by the English while on a social visit, and was held hostage at Jamestown for over a year. During her captivity, a twenty-eight-year old widower named John Rolfe took a special interest in the attractive young prisoner. As a condition of her release, she

had to marry Rolfe (who later became famous for commercializing tobacco). In April of 1614, Pocahontas became Rebecca Rolfe. Soon they had a son whom they named Thomas Rolfe.

The descendants of Pocahontas and Rolfe were known as "The Red Rolfes."

In the spring of 1616, John Rolfe took her back to London where the Virginia Company of London used her in a propaganda campaign to support the new colony. She was wined and dined and taken to theaters. The experience weakened her health and made her ill.

John Smith was also in London, and apparently had a habit of telling stories of being rescued by beautiful women. Three such stories have been recorded, none of them likely. Now that Pocahontas was famous, he apparently made up a similar story about her. Upon a chance encounter with Smith, she was so furious at him that she turned her back to him, hid her face, and went off by herself for several hours. Later in a second chance encounter, she called him a liar and showed him the door.

Rolfe and his young family set off for Virginia again in March of 1617, but Matoaka was very ill and was let off at Gravesend, a name which proved prophetic for her. She died there on March 21, 1617, only twenty-one years of age. Her grave was destroyed in a reconstruction

of the church. [Singer Wayne Newton, who is of Powhatan ancestry, announced in April 2000 that he would cover expenses to find the remains of Pocahontas. (See Wayne Newton)]

"Pocahontas" became much more famous in London after her death, and John Smith apparently elaborated on the "rescue" yarn to no end. According to Chief Roy Crazy Horse,

a descendant of Powhatan, and the source for much of this material, John Smith’s own men described him as "an abrasive, ambitious, self-promoting mercenary soldier." Not someone you’d want to buy a used legend from.

Powhatan died one year after his daughter, in the spring of 1618. Throughout her short life (she died at the age of 22), . Pocahontas tried to promote peace between the Powhatans and the English colonists. She even converted to Christianity and married John Rolfe, a Jamestown colonist, a union which helped bring the two groups together. Her untimely death in England hurt the chance for continued peace in Virginia between the Algonquians and the colonists

Simon Pokagon (Potawatomi).

Simon Pokagon (Potawatomi). Born in Indiana in 1830, he moved to Michigan while young and ended up at Notre Dame for three years. He became Chief of the Potawatomi in Michigan and became well known as part of a delegation to Washington, D.C. His article

“The Future of the Red Man” is very eloquent and insightful about the future, demonstrating an uncommon knowledge of history. His books include Algonquin Legends of South Haven (1900), Birch Bark Booklets (6 volumes) (1899), Pattawattamie Book of Genesis: Legend of the Creation of Man (1901), Red Man’s Greeting (1893), and The Red Man’s Rebuke (1893). He died in 1899.

Joseph Polis (Penobscot). Joseph Polis is quoted at length in Henry David Thoreau’s seminal book The Maine Woods. This partially educated hunting guide related to Thoreau the stories and teachings of Penobscot non-violence and civil disobedience. Thoreau was later asked to give a speech to a local club in Concord, and spoke about these techniques as ways that Americans could protest the various wars that were going on. The speech was later published in

a newsletter, and then in a book, which did not do well. Both Gandhi and Martin Luther King, Jr. were very moved by Thoreau’s writings on the subject, but apparently never read The Maine Woods. Thoreau described Polis as "one of the most enlightened men he’d ever met," and that coming from a friend of Emerson.

Thoreau tells us Polis could made a spruce-bark canoe in a single day, and that he learned new skills with remarkable speed. He was incredibly observant, and once found a cache of hunting traps buried under a log just before nightfall. He showed Thoreau many Algonkeean skills, such as writing on the back of birchbark with the twig of a black spruce, which leaves a clear mark. Polis was not only amazingly agile in an athletic sense, he was agile with a canoe, forging his way up streams and small waterfalls with ease. But his knowledge of traditional Algonkeean diplomacy touched the life of everyone reading this maskweedayg’n birchbark writing today.

Pontiac aka Wandeeak (Ottawa).

Pontiac aka Wandeeak (Ottawa). Pontiac was a great leader and Ottawa Chief who created the "Great Lakes" confederacy in 1762, sometimes called the "Ottawa Confederacy," although it was not the first one. “Pontiac’s War” lasted from 1762 to 1764, and his leadership united native nations from Lake Superior to the Gulf of Mexico, including the Seneca, Delaware, Shawnee, Ottawa, Ojibway, Potawatomi and Huron. In the spring of 1763, his warriors attacked every British fort and installation simultaneously, with great success, capturing nine out of eleven forts along the Great Lakes.

Pontiac was involved with planning the famous siege of Michilimackinack, in which his men were playing LaCross or "Bigattaway," outside the fort, then tossed the ball over the stockade wall, ran inside and killed twenty-one of the thirty-five soldiers there. Later, he planned the siege of the fort at Detroit, but was betrayed, probably by the wife of a white trader who overheard the plan. By the time he arrived for the diplomatic meeting, the sentries had been doubled. He called off the attack, and for the first time, lost a lot of the momentum and confidence of his war party. His second attempt failed as well. He decided to hang tough to preserve the unity of his men, but Amherst held tougher. War escalated quickly from there.

In the end, two thousand settlers were killed, and an untold number of natives.

The main focus of Pontiac’s Rebellion was the British fort at Detroit, an important site spiritually for the Algunkeean people. The siege went on until October 30th, nearly six months.

The French never came to his aid as promised, and when the news of the Treaty of Paris of February 10th, ending the French and Indian war, finally made it to America, Pontiac was left high and dry. However, the battle gained him a great victory. A new proclamation from the English in 1763 declared all land west of the Appalachian/ Allegheny Mountains to be Indian land, and the anti-Indian Sir Jeffrey Amherst was recalled to England.

Pontiac wandered five years throughout the mid-west. He was assassinated in Kohokia in 1769 at a trading post by a Peoria of the Illinois Confederacy, who was presumably hired to do so. It is believed the man was the nephew of Peoria Chief Black Dog.

Pontiac was a supporter of The Delaware Prophet (who has no other name) who had a vision in which the Creator said, "Tell the native people to take back the land I have created for them, and let the English go back to theirs." Pontiac realized part of that vision through the treaty of 1763. In the end, however, many of the results of the war were not what the Prairie nations had in mind. Many of his own best men, including many of his best friends and relatives, were dead, and the retribution of the whites was extensive. The Prairie nations remained disunifed for a generation until Tecumseh, who was one year old when Pontiac was killed, rose to take his place and in many ways, outshine him.

Powhatan aka Wahunsonacook (Chickahominy). 1550-1618. Powhatan’s father had formed a great confederacy of Virginia Algunkeeans which included the local Shawnee, the Mataponi, and at least thirty other tribes, spanning over 200 villages. Wahunsonacook, or Powhatan, after the name of his village, meaning "Falls of the River," was one of the most

king-like figures in Algunkeean history, and was at one time crowned by John Smith as "King Powhatan." He reveled in power and used it wisely to defend his people from attacks from their Iroquois and Siouxan enemies, which were very militant in that time and place.

The English colony of Virginia was one of the more ambitious, and even declared war on the Maryland colony, who were Catholic, and on French colonies further north. Apparently, they were not good neighbors to Powhatan either. The Virginians were constantly demanding free food from Powhatan, so in 1607 he had John Smith captured and brought to him. Nonetheless, they formed a wary alliance out of mutual displays of mistrust, power and authority. Over time they became friendly rivals. He is the founder of the city of Richmond, Virginia.

Powhatan’s brother Opechancanough did not hold the same gift for diplomacy, and though he remained "King" until over a hundred years old (he was assassinated in 1646 as a centenarian) he was only able to hold the Great Peace for four years. Unable to forgive the offenses of the colonists, a huge series of bloody "Powhatan" wars broke out that weakened both sides. Powhatan’s son could not hold the far-flung empire together for long.

Joe Pye (Stockbridge Mohican). The herb Eupatorium fistulosum of the Aster family is named after this herbalist doctor of the Stockbridge Munsee Band of Mohican Indians.

Queen Allaquippa (Lenape/Seneca). According to author Peter Copeland, "Queen Allaquippa" was a Delaware woman, but most sources say she was Seneca (including George Washington), and her children became leaders of the Seneca, unlikely offspring for a Delaware mother, though not out of the question. On New Year’s Day of 1754 the elderly woman accepted gifts from a young British officer named George Washington at Delaware Village in western Pennsylvania. They had dined together in 1848. Washington had accidentally "snubbed" her on his ride through the area the month before. This time he brought her a matchcoat and a bottle of rum, which were well received.

The British were eager to prevent her people from forming an alliance with the French. However, during the ensuing war, the English, with the exception perhaps of William Johnson, treated the native people with such contempt that no alliance could be maintained for long. When the Revolution was ending, George Washington, now an American officer, led the charge to destroy Seneca, Mohawk, and other Iroquoian villages. He became known thereafter to native people as "Lenatagadeaas," a Mohawk word that means "He wrecks the town."

The town of Aliquippa, in Beaver County, Pennsylvania, was named after Queen Allaquippa, a great community builder in a time of war.

James Lone Bear Revey (Lenape)

James Lone Bear Revey (Lenape) was a great 20th century Chief. It was his father who was the last chief of the Delawares who stayed behind in New Jersey. The Sand Hill Lenape, based near Neptune, New Jersey dissolved their tribal council in 1953 after outmigration and assimilation had dwindled their numbers.

Roy Rogers aka Leonard Slye (Meskwakee).

Roy Rogers aka Leonard Slye (Meskwakee). A Native American from Ohio, Roy Rogers was from the Meskwakee (also spelled Mesquakie and otherwise) people. He is known for his cowboy movies and a lot of fast food. His wife Dale Evans is also a major talent, but she has never announced a tribal affiliation as far as I know. Two of the other members of Roy’s

“Sons of the Pioneers" musical group, Carl and Hugh Farr, were also Native American.

Slow Turtle (Pequot).

Slow Turtle (Pequot). A controversial chief and leader of the Pequots, Slow Turtle helped lead them to establishing the Foxwoods Casino, creating a financial base which helped fund a large Native American museum and research library.

Smoking Star (Blackfoot). This elder’s teachings were partly preserved in writing by Clark Wissler of the American Museum of Natural History. At that time, Smoking Star was ninety, and the eldest of the Blackfoot. His name refers to what the white man calls the planet Mars.

Andrew Sockalexis (Penobscot).

Andrew Sockalexis (Penobscot). Brother of Louis Sockalexis, Andrew was a champion long distance runner. He took second place in the Boston marathon in 1912, the year before Louis died.

Louis Sockalexis (Penobscot),

Louis Sockalexis (Penobscot), an outfielder for the Cleveland Spiders baseball team, had developed an extraordinary arm hurling rocks across a lake on the Indian Island Reserve near Old Town Maine. He became a college star at Holy Cross and then with the famed Notre Dame. He and a classmate were expelled from Notre Dame in 1897 due to drinking problems. Apparently, they smashed up a local bordello. Patsy Tebeau, manager of the Cleveland Spiders, bailed them out and hurried Sockalexis onto the team.

Sockelexis started well and so impressed the legendary successful manager John McGraw that he pronounced Louis the greatest natural talent he had ever seen. But drinking was his downfall. He was soon sidelined after injuring his ankle; rumor said it was from leaping from the second story window of a brothel.

Sockalexis played parts of two more seasons and hit .313 before alcohol and the aggravated injury forced him from the majors. (I believe 1900 was his last season.) Until his death in 1913 at age forty-two, he taught Native American boys on the Penobscot Reservation how to play ball. When Sockalexus was found dead, yellowed press clippings from his brief career were found in his shirt pocket.

There is much controversy surrounding the actual date when the team name was changed and why. According to some sources, sportswriters named Sockalexis "The Cleveland Indian" while he played ball. According to other sources, Cleveland fans voted to rename their team The Cleveland Indians "in his honor," as they claimed, within two years after his early retirement,

so that Nap LaJoie led the American League in its first year in existence, 1903, batting .355 as

a "Cleveland Indian." The Sporting News Baseball Chronicles report this as the name of the team that year (page 12) According to other sources, the name was The Naps (after Nap LaJoie) from 1903 until LaJoie’s trade to another team a few years later. According to other sources, the team was never called The Cleveland Indians until two years after Sockalexis’ death.

Although poor, saddened, and with no future in baseball, Louis enjoyed ten years as the living namesake of the Cleveland Indians, that is, depending on who you believe.

I doubt that during those years there was much "Tomahawking," and the unfortunate logo of the "screaming Indian" came much later. If they really want to "honor" the "Indians," they should have an actual picture of Louis Sockalexis on their caps. It would add to the public’s knowledge, rather than distort it.

Squanto aka Tisquantum (Patuxet). The Patuxet were the Algunkeeans living in the area later called Plymouth by the colonists. Most of them were wiped out by disease before 1620 with the notable exception of Squanto, who had been captured by the English sea captain Thomas Hunt and taken first to Newfoundland and then England, where he learned to speak fluent English. Squanto returned in 1619 to find all of his kinsmen dead.

In 1620, when the Pilgrims arrived, Squanto was able to greet them in perfect English, although he chose to add a bit of Algonkeen he thought would be understandable to them.

His actual words were: "What cheer, Needap?" ("Needap" means "friend.")

He befriended the colonists and made it possible for them to survive that first cold winter.